Authored by: Dr. Stuart Barclay

A development is only as good as its future readiness. To help test that, we ask two questions:

1. Can the development’s site support low-impact, low-cost living throughout its life cycle?

2. Can the development’s residents reach jobs, services, and recreation without long car trips?

Location intelligence can help answer these questions by applying the Sustainability and Accessibility indices.

Missed the earlier instalments?

All these together form Geoscape’s seven-point lens on housing feasibility.

How Location Intelligence Helps

Location data helps bring the Sustainability and Accessibility two indices to life. It identifies rooftops with the highest solar yield, nearby battery corridors, and ridgelines suited to small-scale wind so renewable systems can be sized accurately.

This same data can identify current rail, bus, cycling, and road networks, revealing lower-cost upgrade options that can help reduce travel times and emissions.

Forward-looking demographic and climate models then stress-test designs to 2050, flagging layouts likely to struggle with heat, flooding, or regulation long before construction begins.

Why It Matters

Projects that miss on Sustainability or Accessibility can lock residents into higher bills, stranded assets, and daily inconvenience. Early spatial insight uncovers those risks and channels capital toward designs and locations that will hold their value.

What data makes up these two indices?

Sustainability

The energy efficiency of a home is data considered within the Sustainability index. Source: Shutterstock

Sustainability in housing means designing, constructing and operating homes in ways that balance environmental health, economic viability and occupant wellbeing over the long term.

This can be achieved by considering:

1. Environmental Performance

• Energy efficiency: Minimising operational energy usage through high‐performance insulation, airtight construction, passive solar design, efficient heating/cooling and on-site renewables (e.g. rooftop solar).

• Water efficiency: Reducing potable water use via low‐flow fixtures, rainwater harvesting, and greywater reuse.

• Materials and embodied carbon: Choosing low-impact, responsibly sourced materials (e.g. Forest Stewardship Council-certified timber, recycled steel), minimising embodied carbon through design for reuse, and avoiding toxic finishes (e.g. CCA-impregnated timber).

• Site and biodiversity: Integrating homes into the natural landscape with minimal disruption, preserving native vegetation, and incorporating green roofs or walls.

• Internal environment quality: Ensuring good daylighting, thermal comfort and ventilation.

2. Economic Resilience

• Lifecycle cost savings: While initial costs for high‐performance features or high-quality construction may be higher, reduced utility and maintenance bills deliver payback over the home’s lifetime.

• Durability and adaptability: Designing for longevity (robust cladding, flood resilience) and flexibility (spaces that can adapt as household needs change) to avoid building obsolescence.

• Affordability and accessibility: Balancing environmental features with cost so that sustainable homes remain within reach of diverse income groups, including universal design for ageing in place.

Examples of real-world improvements in housing sustainability are:

• Australian rooftops already have more rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity than every coal generator combined, passing 25.5 gigawatts (GW) of solar PV capacity in 2024 (Source).

• Since the introduction of BASIX (Building Sustainability Index) in 2004, new homes in NSW have been required to reduce potable water consumption by up to 40% compared to pre-BASIX standards. This is typically achieved by the installation of rainwater harvesting and greywater systems in new-build housing (Source).

A shift towards sustainable housing not only reduces the environmental and economic impact of new housing, but also makes homes more attractive to buyers navigating tighter budgets and tougher energy regulations.

Accessibility

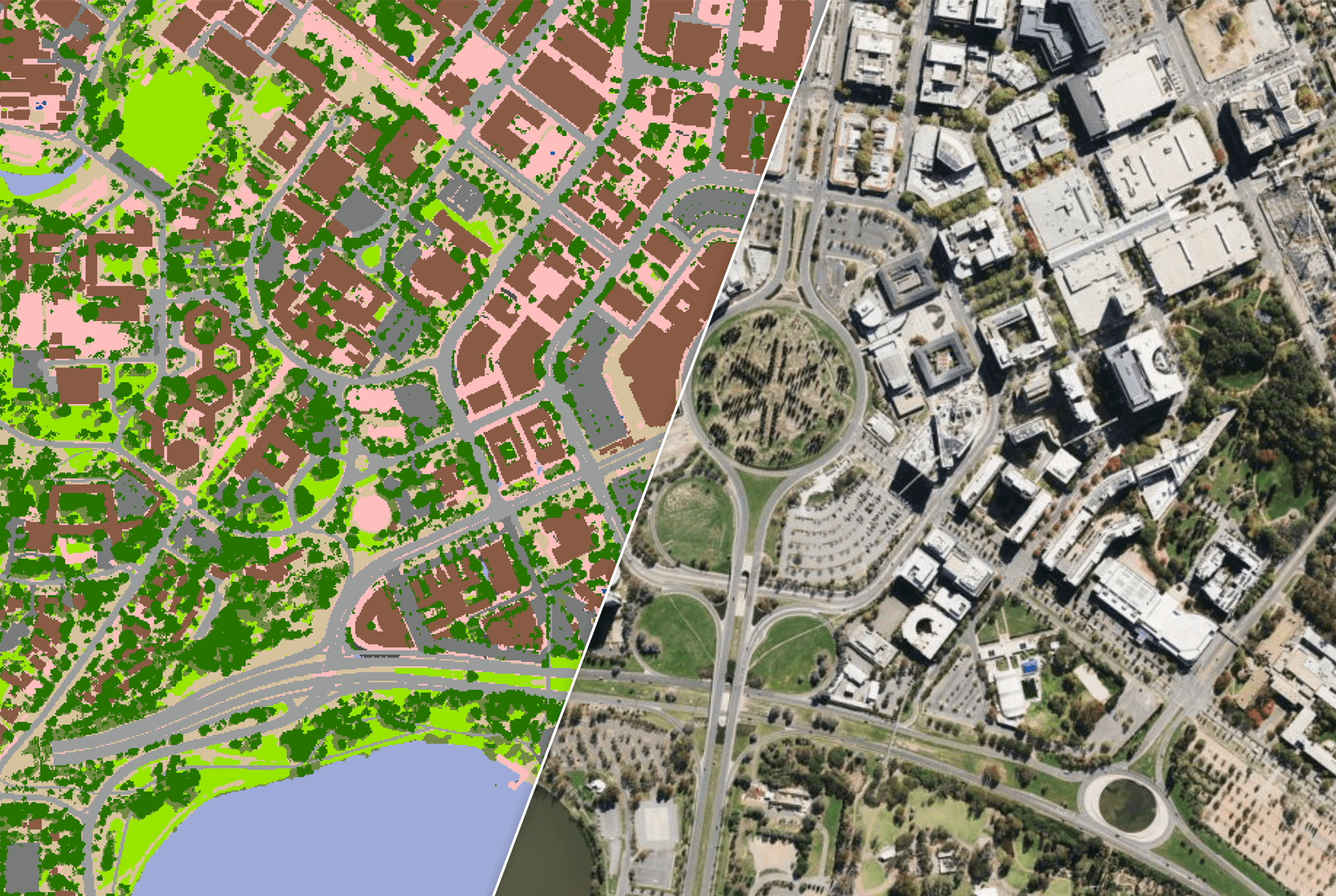

Quality access to public transport is data considered in the Accessibility index

Here, housing accessibility is used to describe how a house is located in terms of its connections to services and transportation. The primary needs for most people are to be able to access shops, schools and their places of employment.

Typical considerations for housing accessibility include:

1. Proximity to Daily Needs

• Employment centres: Short commutes reduce travel time, stress and greenhouse-gas emissions. Ideally, a home sits within a 30-minute commute of place of employment (Source).

• Retail and services: Access to services (retail, education and medical) within walking distance (generally within 400m or approximately 5-minute walk) supports daily life without reliance on cars (Source).

2. Public Transport Connectivity

• Transit-Oriented Development (TOD): Homes clustered around high-frequency bus, tram or train stops enable convenient, low-emission travel. A common benchmark used, is living within 400 m of a stop served every 10–15 minutes during peak hours (Source).

• Multimodal integration: Seamless connections between transport modes (e.g. cycling to a park-and-ride, bus to train) widen the range of reachable destinations and increase the usefulness of public transport.

3. Walkability and Active Travel

• Pedestrian networks: Well-constructed pavements, pedestrian road crossings and minimal barriers encourage walking.

• Cycling infrastructure: Protected bike lanes, secure end-of-trip facilities and bike-share hubs make cycling a viable choice for a broader segment of the population.

4. Equity & Inclusion

• Affordability built into accessible areas: Ensuring lower-cost housing is available near transit and services prevents socio-economic segregation and “transport poverty” where low-income households spend a disproportionate share of income on travel.

• Universal design: Accessible routes, lifts and tactile paving help people with mobility impairments or sensory disabilities navigate public spaces and transit.

5. Resilience & Flexibility

• Redundancy in connections: Multiple transport options mean that if one transport mode is disrupted – by extreme weather or maintenance – residents still have the ability to reach services or employment.

A 2024 analysis by the Climate Council found that only about half the population in Australia’s five largest cities lives within an 800-metre walk of public transport services that run at least every 15 minutes between 7 am and 7 pm. Brisbane ranks lowest, with just 33.7% of residents having such access (Source)

Strong Accessibility scores go to neighbourhoods where frequent public transport, safe cycling corridors, and essential services sit within a short walk. Shorter commutes cut transport costs, widen job choices, and lower emissions.

Series Wrap-up: The Seven Indices in One Checklist

Geoscape’s housing framework in its entirety is:

1. Liveability

2. Desirability

3. Suitability

4. Vulnerability

5. Insurability

6. Sustainability

7. Accessibility

By applying location intelligence to each factor before the first shovel hits the soil, the result is homes that are ready on day one, resilient for decades, and within reach of the people who need them.